Not a Level 5

It’s not uncommon to see someone build a small working demonstration or design a user interface for an aspect of managing healthcare. From managing your own personal healthcare data to a “complete” electronic health record, you’ll see it all.

Having worked at Epic for 25 years, I have had some experience with healthcare software from patient/consumer access (MyChart) to the core databases running the Epic system (and so many moving parts between). This morning while doing my routine of watching a few YouTube videos while exercising, I started watching a video entitled, “5 levels of UI skill. Only 4+ gets you hired.”

Ok: Pure and utter clickbait. I tapped it and started watching as the draw to find out …, but, I couldn’t stomach the full content after the creator made proclamations of extraordinarily subjective measures of people and their designs: five levels?

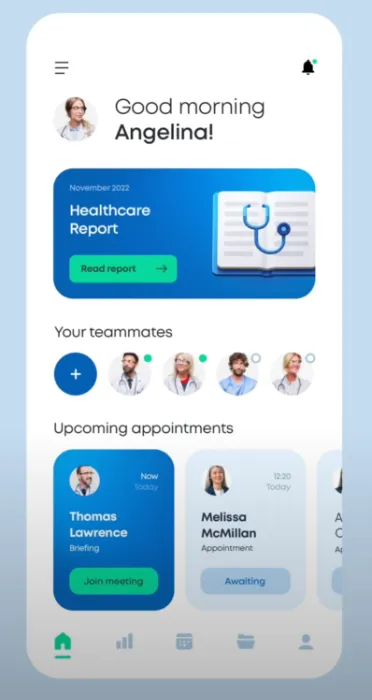

The aspect of the video that caught my attention and raised my alarm for “this is utter nonsense” was the self-proclaimed, level 5 application. Here’s a snapshot:

If you’ve worked at Epic, or in healthcare in nearly any capacity, I suspect you may see why this “Level 5” application design is so poor.

I’m confident the author thinks this is an award winning application. If you ignore the giant-roundness of everything, let me show something by way of a list:

- Menu button probably

- An alarm with a green dot

- Good morning Angelina and photo of Angelina

- November 2022 Healthcare Report > Read Report

- Your teammates (4 images teammates), and a add/plus button

- Upcoming Appointments:

- Now, Today, Thomas Lawrence, Briefing > Join Meeting

- 12:20 Today, Melissa McMillan, Appointment > Awaiting

- A row of unlabeled icons:

- Home, Graphs?, Calendar, Folder?, Person

That’s it. A full application screen.

Comments

- An entire mobile screen with very limited information. There’s no concern of having too much to do on this screen.

- The application places no importance on data density or relevance to important tasks.

- How long has “Healthcare report” been available? Is it new? Why is it appearing there? Why does Angelina care?

- Can a user dismiss the report if they aren’t interested or have already read it?

- Decide on a meaningful report name and use that in an example rather than “healthcare report.”

- Is the “healthcare report” more important than the briefing that Angelina is apparently due for right now?

- Only 2 appointments fit on the screen, and still provide basic to no helpful information about each appointment.

- The second appointment listed is an “appointment?” That information was obvious from being in a list of appointments. “Virtual exam.” “Wellness Visit” … nearly anything would have been a better choice than “Appointment” in a list of appointments.

- I wonder how long an appointment is.

- It appears that there’s no way to scroll back to see the appointments Angelina had (but I’ll say maybe, but I doubt it as there’s no visual hint that would work). Have they missed an appointment or want to review them using the same user experience that they use to see upcoming appointments?

- There’s a button saying “awaiting” on the second appointment. Is that an action: “awaiting” someone? Or is it a status? The giant appointment slot to the left suggests the rectangular shape is an actionable button, but with the second one saying “awaiting” it’s not clear.

- Does the user need a giant “Good morning Angelina?” In a business setting, it’s wasted space for someone who is likely rushing from task to task. After seeing that on the 2nd day, I’d want to disable that feature FOREVER.

- Even if this app were being used on a shared device with authentication for a current user, the space taken by the avatar and the greeting is very much wasted.

- Does Angelina need a large daily reminder of what they looked like when their staff photo was taken 5 years ago?

- What unusual workplace would Angelina be in where adding a teammate would be important enough to warrant reserving space for that action on this screen?

- Who are these “teammates” anyway? That might align with some clinical situations, but I doubt it. I would expect the list to change based on scheduling, care teams, etc. Having only photos for staff is frustrating as it’s very common that staff photos are poor and out of date. Hair, beards, age, glasses …, and at a small size, they tend to look too similar. In most work environments (including healthcare), you don’t choose your teammates.

- I presume that the images of teammates with what probably is their status is an actionable button. It’s a mystery.

- Does the likely status circle mean they’re not busy if it’s green? Or they’re in an appointment? Or at lunch? Or out of the office? Or in a briefing … it better not just be color alone that indicates the status.

- There’s an avatar image on appointments, is that also an actionable button?

- What happens when the list teammates is longer than 4? Does the list scroll? Is that useful?

- The affirmation that “Now” is also today …, but what would it say if Angelina was 5 minutes late?

- The blue background color seems to be used for important actions, yet the “Add to Teammates” button is also blue.

- I would have expected to see some way to see messages from other teammates and coworkers on this screen, in addition to their “in box” of clinical messages that aren’t chat-like.

- This application would be difficult to localize as is, I would expect text wrapping issues in many languages.

I couldn’t think of a single application I use routinely in any capacity that fails as much as this mock/application has.

On Levels

To suggest that there are “levels” and the only real way to get hired is to X, Y, & Z is a load of 💩. The author creates courses that they want you to buy: Achieve Level 5!

I’d instead say an app that looks good but doesn’t provide the functionality the user needs for their job is a failure. Since it’s all subjective anyway, I’d give this app design a 1.

Instead, my basic advice:

Practice your skills. Get feedback. Keep at it. Practice. Listen. Watch videos, but watch/listen with a critical eye. Even taking the time to mentally make a list of what you’d change about a design you see can help you grow and learn.

Summary

Don’t watch the video.

Overall, this is a sloppy attempt at click-bait and application design for a well-known industry. A moderate amount of research into the responsibilities of Angelina’s role would have provided a much better guide for a purpose built application/design.

If you’d like your application reviewed, I have a service where I provide that. Save yourself a lot of time and frustration by having your app design reviewed BEFORE your engineers spend weeks or months implementing it. I can go a lot deeper and broader than I’ve done here. I can talk pixels and typefaces and colors and …😀.